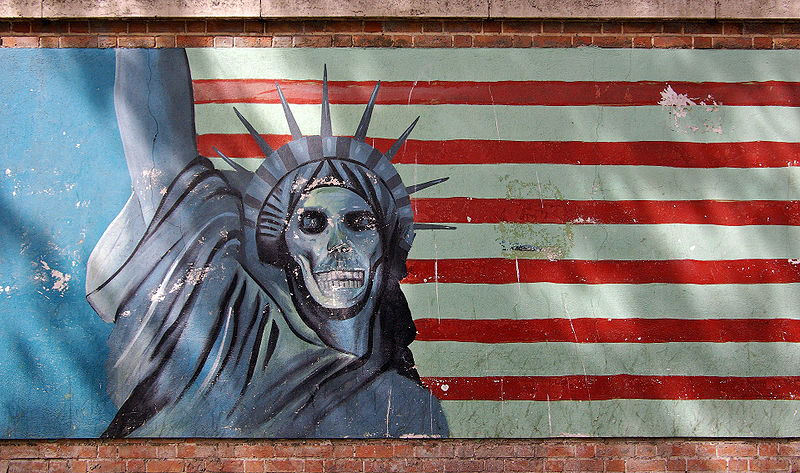

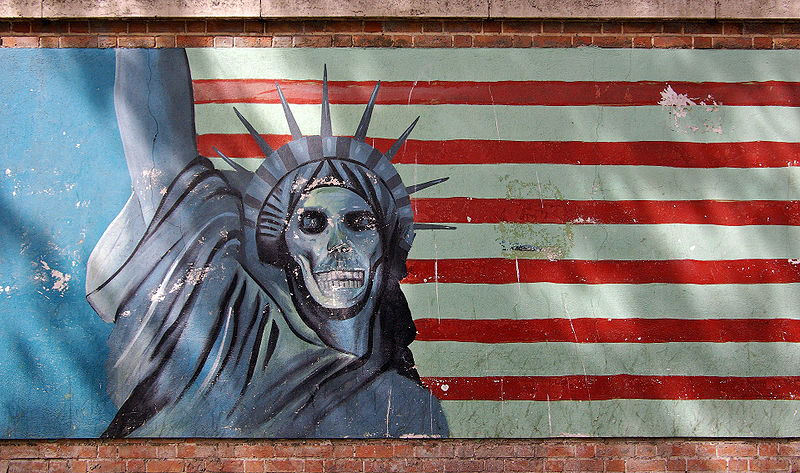

The Obama administration’s diplomacy with Iran over its nuclear program is in shambles. In the broadest terms, this is because the so-called diplomatic opening Obama initiated upon coming into office never actually happened; Washington has been more apt to continue to bully Iran diplomatically while using draconian economic warfare to squeeze the Islamic Republic, despite Washington’s inability to identify any substantive Iranian transgressions.

But there is another, more specific detail to this story that is obstructing any political deal between Iran and the US (the P5+1 are there only to repel the impression that the US is actually engaging with Iran). And that detail is the obsession that the UN’s International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has with the Iranian military site Parchin.

Yousaf Butt, a nuclear physicist and professor at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies at the Monterey Institute of International Studies, writes about this absurdity in Foreign Policy:

Following two days of talks last week, officials from Iran and the IAEA threw in the towel, failing again to clinch a deal on access to sites, people, and documents of interest to the agency. The IAEA’s immediate priority is to get into certain buildings at the Parchin military base near Tehran, where they suspect Iran may have conducted conventional explosives testing — possibly relevant to nuclear weaponry — perhaps a decade or so ago. There is no evidence of current nuclear work there (in fact, the agency has visited the site twice and found nothing of concern). But by inflating these old concerns about Parchin into a major issue, the agency risks derailing the more urgent negotiations that are due to take place between Iran and the P5+1 countries (China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Germany).

The IAEA again wants access to the site because of secret evidence, provided by unidentified third-party intelligence agencies, implying that conventional explosives testing relevant to nuclear weaponization may have taken place a decade or so ago at Parchin. The agency has not showed Iranian officials this evidence, which has led Iran to insist that it must have been fabricated. (This could well be true, given that forged documents were also passed on to the IAEA before the 2003 Iraq war.) As Robert Kelley, an American weapons engineer and ex-IAEA inspector, has stated: “The IAEA’s authority is supposed to derive from its ability to independently analyze information….At Parchin, they appear to be merely echoing the intelligence and analysis of a few member states.”

Olli Heinonen, the head of the IAEA’s safeguards department until 2010, is also puzzled at the way the IAEA is behaving: “Let’s assume [inspectors] finally get there and they find nothing. People will say, ‘Oh, it’s because Iran has sanitized it….But in reality it may have not been sanitized….I don’t know why [the IAEA] approach it this way, which was not a standard practice.” And Hans Blix, former head of the IAEA, weighed in, stating, “Any country, I think, would be rather reluctant to let international inspectors to go anywhere in a military site. In a way, the Iranians have been more open than most other countries would be.”

This last point is corroborated by Flynt Leverett and Hillary Mann Leverett in their new book Going to Tehran: Why the United States Must Come to Terms with the Islamic Republic of Iran, in which they report current “agency [IAEA] officials have told us they have better access to these [Iran’s nuclear] facilities than to analogous sites in some Western countries.” These inside accounts by experts in the field run in stark contrast to the media hype that Iran is somehow blocking IAEA access to facilities that could be hiding work on nuclear weapons.

But this isn’t the case. The IAEA doesn’t have jurisdiction over military sites like Parchin. They are being insistent on the Parchin issue despite having full access to all of Iran’s declared nuclear facilities and confirming time and again the non-diversion of Iran’s nuclear material.

But this isn’t the case. The IAEA doesn’t have jurisdiction over military sites like Parchin. They are being insistent on the Parchin issue despite having full access to all of Iran’s declared nuclear facilities and confirming time and again the non-diversion of Iran’s nuclear material.

And anyways, the allegations of weapons development at Parchin are that Iran was conducting work there a decade ago. Not only is that irrelevant to whether Iran is currently conducting weapons development, but even if it were true (which, again, is highly questionable) “Iran would not have violated its IAEA safeguards agreement,” Butt writes.

That said, the IAEA’s peculiar approach, under the self-described pro-US chief Yukiya Amano, is not the only roadblock. Most of Obama’s so-called diplomacy with Iran has been “predicated on intimidation, illegal threats of military action, unilateral ‘crippling’ sanctions, sabotage, and extrajudicial killings of Iran’s brightest minds,” writes Reza Nasri at PBS Frontline’s Tehran Bureau. This, despite a consensus in the military and intelligence community that Iran is not currently developing nuclear weapons and has not even made the political decision to do so.

Two experienced academics and diplomats, writing in Foreign Affairs back in October, also found the so-called diplomatic opening Obama brought was anything but: “for the past three years, the United States and Europe have stubbornly refused to seek a negotiated solution with Iran.”

Rolf Ekéus, Executive Chairman of the UN Special Commission on Iraq from 1991 to 1997, and Målfrid Braut-Hegghammer, Stanton Nuclear Security Junior Faculty Fellow at the Center for International Security and Cooperation at Stanford University, write that “calling for war while intensifying pressure on Iran, without also clearly defining steps Tehran could take to defuse the tension, removes any incentives for Iran to change its behavior.”

The last carrot the US offered Iran was spare parts for civilian airplanes, a pathetic offer they must have known Iran would (justifiably) balk at.

As Butt notes, former CIA analyst Paul Pillar has pointed out that the sanctions are “designed to fail.” Congress’s legislation links the sanctions to a long list of Iranian policies not at all related to their nuclear program. This makes lifting them really difficult in the context of nuclear negotiations.

After the failed talks in 2009 and 2010, wherein Obama ended up rejecting the very deal he demanded the Iranians accept, as Harvard professor Stephen Walt has written, the Iranian leadership “has good grounds for viewing Obama as inherently untrustworthy.” Paul Pillar has concurred, arguing that Iran has “ample reason” to believe, “ultimately the main Western interest is in regime change.”

After the failed talks in 2009 and 2010, wherein Obama ended up rejecting the very deal he demanded the Iranians accept, as Harvard professor Stephen Walt has written, the Iranian leadership “has good grounds for viewing Obama as inherently untrustworthy.” Paul Pillar has concurred, arguing that Iran has “ample reason” to believe, “ultimately the main Western interest is in regime change.”

In their Foreign Affairs article, Ekéus and Braut-Hegghammer say explicitly that they think the sanctions have “the long-term objective of regime change,” not a diplomatic settlement. Back in the 1990s, when the US-led sanctions regime in Iraq was killing millions of innocent people, Saddam’s regime actually met the Security Council requirements to get the sanctions lifted, but the US refused to provide any sanctions relief. When the sanctions were imposed, Washington insisted they were about blocking Iraq’s nuclear program. Then, “In the spring of 1997,” the authors write, “former US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright gave a speech at Georgetown University in which she stated that even if the weapons provisions under the cease-fire resolution were completed, the United States would not agree to lifting sanctions unless Saddam had been removed from power.”

This is why a deal with Iran has not been forthcoming. Tehran knows and understands this. As Ayatollah Khamenei said in August 2010, “If they [the US] do not resort to bullying and step down from the ladder of imperialism…we will not have problems with negotiations. But negotiations are impossible as long as they behave like this.”

“President Obama and everyone here knows that American foreign policy is not defined by drones and deployments alone,” Kerry said.

“President Obama and everyone here knows that American foreign policy is not defined by drones and deployments alone,” Kerry said.

Nasr, born in Tehran, is

Nasr, born in Tehran, is  United Nations had developed a monitoring system designed to detect Iraqi violations of the nonproliferation requirement,” report two high level diplomats in

United Nations had developed a monitoring system designed to detect Iraqi violations of the nonproliferation requirement,” report two high level diplomats in

But this isn’t the case. The IAEA doesn’t have jurisdiction over military sites like Parchin. They are being insistent on the Parchin issue despite having full access to all of Iran’s declared nuclear facilities and confirming time and again the non-diversion of Iran’s nuclear material.

But this isn’t the case. The IAEA doesn’t have jurisdiction over military sites like Parchin. They are being insistent on the Parchin issue despite having full access to all of Iran’s declared nuclear facilities and confirming time and again the non-diversion of Iran’s nuclear material. After the failed talks in 2009 and 2010, wherein Obama ended up rejecting the very deal he demanded the Iranians accept,

After the failed talks in 2009 and 2010, wherein Obama ended up rejecting the very deal he demanded the Iranians accept,