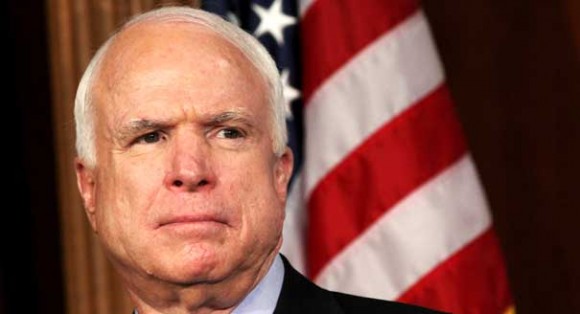

In July 2012, Senator John McCain argued the US’s unwillingness to intervene militarily in Syria to stop a humanitarian catastrophe was “shameful and disgraceful,” because it has allowed Bashar al-Assad “to massacre and slaughter people and stay in power.” Last month, he called on the US to “lead an international effort” to conduct “airstrikes on Assad’s forces.”

“The Assad regime has spilled too much blood to stay in power,” McCain insists.

McCain’s interventionist allies in Congress have been making similar pleas in Washington to initiate military action to stem the Assad regime’s violent crackdown on an armed rebellion. Hawks in the media, like Max Boot and Jackson Diehl, have just this week argued that 70,000 dead – according to a United Nations estimate – is too much not to intervene.

I’ve written ad nauseam and in detail about how disastrous direct US military intervention in Syria would be. Everything from directly arming the rebels to imposing a no-fly zone to sending boots on the ground to topple the Assad regime – all of it carries the predictable consequence of making the humanitarian situation unimaginably worse, which is ironic for war hawks who justify intervention on humanitarian grounds.

But we can expose the weak and even dishonest case for military action in Syria in a much simpler way: by analogy.

Last week, The Daily Beast covered the trial of Rios Montt, “the first former head of state ever to be tried in his own country for actions committed during his rule,” in Guatemala in the 1980s. Montt and his former military intelligence chief, reported Mac Margolis, “stand accused of genocide and ‘crimes against humanity.'”

Montt came to power in a military coup and “was a close ally of Washington who received training at the infamous ‘School of the Americas,'” writes Cyril Mychalejko. The Reagan administration “not only covered up, but aided and abetted war crimes and genocide in Guatemala.”

“Perhaps half of all those who died during the conflict, 100,000-150,000, died between 1981 and 1983,” according to Mike Allison, Associate Professor of Political Science at The University of Scranton.

So in a matter of two or three years, about 150,000 people were killed in a war that was being waged primarily by US-backed war criminals. Less than half that many have been killed in the same amount of time in Syria.

Why weren’t war hawks in Washington calling for the US to militarily intervene to unseat the Guatemalan regime in 1983? Better yet, why wasn’t anybody blaming the Reagan administration for paling around with blood-soaked dictators of exactly the type McCain, Boot, and Diehl now accuse Assad of being? Or better still, why isn’t anyone calling for accountability for the still-living Reagan administration policymakers, say Elliot Abrams, who insisted on maintaining US support for people like Rios Montt?

It’s hard to come to any other conclusion: interventionists in Washington who couch their arguments for military action in humanitarian terms are simply not using human suffering and death counts as a criteria for US intervention. Instead, they conveniently exploit instances of conflict and human suffering when it occurs in countries that they’ve long desired to intervene in anyways.

In 1994, something like 500,000 people were killed in Rwanda in a matter of 100 days. But McCain wasn’t going on television demanding President Clinton invade. Maybe 400,000 civilians died in the Darfur conflict, only petering out in very recent years. Few on the right called for a bombing campaign to eliminate the perpetrators.

Syria is strategically located in the Middle East, is geographically a close neighbor of Israel and a close ally of the recently-empowered-by-the-bungled-Iraq-War, Iran. President Bashar al-Assad is an ally of the Russians who value their last close ally in the region because it affords them geo-political influence and a chance to defy US imperialism. And this is why the conflict in Syria is being used to justify intervention. Not because of the death count.