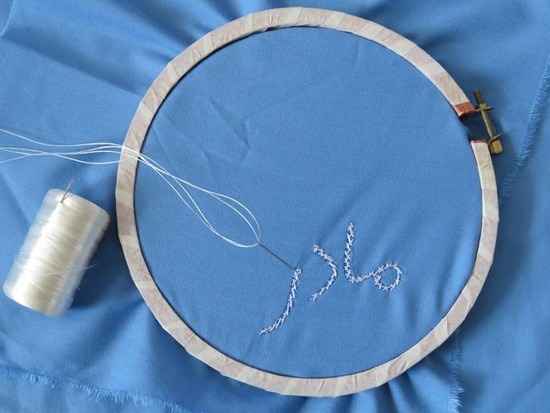

When activists like me return from visiting the Afghan Peace Volunteers in Kabul, Afghanistan, young seamstresses there often entrust each of us with about fifty sky-blue scarves. The word “Borderfree” is carefully embroidered, in English, on one end of each scarf; on the opposite side, they’ve stitched the translation in Dari, the language they speak. The scarves express their yearning to end four decades of war in Afghanistan, a land dominated by ruthless warlords.

“We are the generation who must try to put an end to all war and violence,” wrote Nematullah, an Afghan Peace Volunteers member who teaches children from internally displaced families. His students, most of them displaced by war, live in a wretched refugee camp.

Nematullah wrote in response to my anxious inquiry following a truck bombing in Kabul, Afghanistan, on May 31, which killed more than 150 people. Pictures from Kabul’s “Emergency Surgical Center for Victims of War” showed his staff ministering to hundreds of survivors, people who suffered burns, lacerations, wounds, and amputations.

Happily, the letter brought good news. “We’re all safe,” wrote Hakim, who mentors the Afghan Peace Volunteers. “Yet we don’t want to ‘get used’ to life in a war zone. War is brutal, and begets more war, again and again.”

After the bombing, some of the volunteers went to work on a permaculture plot they maintain at the Kabul University. They shared a moving image of themselves at work in the field, images of people doing their best to stay human amid war’s traumas.

Over the following days, dozens of Afghans have been killed in attacks across the country, including in Kabul where at least four demonstrators were killed by Afghan armed forces. The demonstration called on the Afghan government to provide greater security for people. The next day, three suicide bombers attacked a funeral for one of the protesters, killing five people and wounding 119.

Some reports say that Kabul has been shut down. Yet sit-ins are being held in multiple spots, across the city, calling on the government to fulfill its role in helping protect people.

Their determination is remarkable. I’m also impressed by the everyday courage and fortitude of so many Afghans who continue to care for one another in their communities.

Afghanistan could truthfully be described as an unruly, failed narco-state. But Hakim asks us to understand that, nevertheless, most of Afghanistan’s estimated 30 million people “are not going around killing one another or killing strangers with knives or guns. In reality, government services are insufficient or nonexistent, so it is people and communities that are making things work day to day.”

Without any input from the centralized government, the Afghan Peace Volunteers build community and share resources. They steadily develop ways to connect with young people in other Afghan provinces. Within Kabul, they arrange inter-ethnic activities and projects, distributing food, educating children, and manufacturing heavy blankets to help families survive the harsh winters. They risk their lives to relate with people whom they are told are their enemies.

The warlords from the west, led by the United States, take a dim view of Afghanistan interacting with neighboring countries Iran, China, and Pakistan. And Russia is not far away. One of the reasons the United States spends so much to maintain bases, weapons, special operations forces, surveillance systems, and detention facilities within Afghanistan is because it wants to communicate a strong message to these neighbors.

“Afghanistan, for Americans, doesn’t really exist as a country and a people,” writes William Astore, a retired lieutenant colonel with the U.S. Air Force. “It exists only as a wasteful, winless, and endless war . . . . It’s a chance to test theories and to earn points (and decorations) for promotion for many officers. It’s hardly ever about working closely with the Afghan people to find solutions that will work for them over the long haul.”

All the more reason for my young friends to send us home carrying armfuls of “Borderfree” scarves. Instead of tolerating endless war in Afghanistan, we need to demand that the United States pay reparations for the suffering and destruction it has already caused. We need to learn from the generation of young volunteers trying to put an end to war.

Kathy Kelly co-coordinates Voices for Creative Nonviolence.

Border Free? Seems that one problem is that Afghanistan is split into so many factions as different ethnic groups have moved in and out of the country, Pashtuns, Persians (Dari is a dialect of farsi), Tajiks, Uzbecks, etc. Also, please note that the demonstrations after the truck bombing called for immediate execution of suspects being held from the responsible group (it wasn’t the Taliban). They weren’t exactly what should be characterized as peace demonstrations. Prior to the US invasion, the Pashtuns ruled over 90% of the country in relative peace. The US utilized other ethnic groups against the Pashtuns which is why the country has degenerated into civil war.

Usually partition is the only short term solution for a problem like Afghanistan. As an exit strategy, the US could pay people to relocate into defensible areas for a fraction of the cost (monetary and human) of continuing the war.