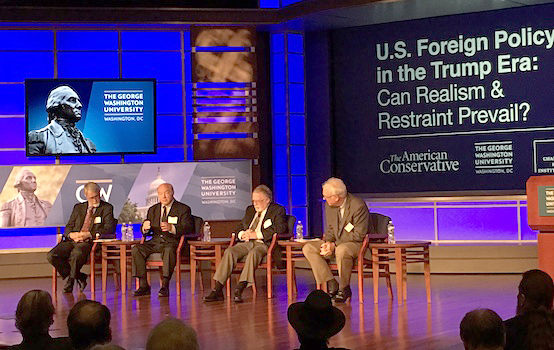

“U.S. Foreign Policy in the Trump Era: Can Realism and Restraint Prevail?” was held Friday morning at George Washington University in Washington, DC. Watch full video here.

WASHINGTON – What is the fate of realism and restraint in the Trump era?

The consensus among the foreign policy luminaries brought together by the American Conservative on Friday: Don’t expect much from the White House, even though global realities, i.e., the ascendency of China, may leave the old U.S. order in the dust.

If there was any hope that Trump would inaugurate a new era of restraint, or even realist thinking, it’s been pretty much overtaken by events. Or, perhaps TAC editor Robert Merry put it best:

“Realism and restraint’ in the Trump era is roughly equivalent to the gigantic ice wall in Game of Thrones after the dragon that came under the spell of the night walkers got through with it,” he said.

That certainly got a laugh from the crowd at George Washington University, but the rest of his remarks about the discrepancies between Trump’s memorable foreign policy speech during the campaign in April 2016, and what he has done so far as president, were anything but funny.

“So many Americans rallied to the Trump campaign because of his hard attacks on the status quo but it turns out he was not the leader to take on the status quo, he just nibbles at the edges of it,” Merry noted, pointing out Trump’s earlier vision about scaling back wars and blasting nation building, only to propose sending more troops to Afghanistan, which has yet to produce a victory – no strong government nor capable Afghan military – in 16 years of U.S. intervention. He also pointed out Trump’s lack of resolve regarding easing tensions with Russia, or putting more pressure on NATO (Merry specifically fingered the expansion to tiny Montenegro, which faces both a backlash here and by the Russian government).

And, “(Trump) said we should have never been in Iraq; we have destabilized the Middle East,” added Merry, “yet now he threatens a confrontation with Iran.”

Asked whether Trump has engaged new and fresh voices in this administration, the answer is decidedly no, according to Will Ruger, vice president of research and policy at the Charles Koch Institute and Cato Institute fellow.

“If you look, leaving aside the people who signed the Never Trump letter, a lot of the same people who are involved (in the administration) are the same old people with the same old ideas,” he said. “That’s the problem.” He did note, more positively, that at least Trump and his Secretary of State Rex Tillerson still talk about the sovereignty of other nations and the problems of “democracy building.”

But what about the other players in the administration? Author and TAC contributor Mark Perry charged that the three generals in the Trump inner circle – Chief of Staff John Kelly, Secretary of Defense James Mattis and National Security Advisor H.R. McMaster – were, despite being called the “adults” in the room, “out of their lane,” and not helping steer the Trump foreign policy in any meaningful way.

“We have a civilian government for a reason. We have political people doing political jobs for a reason. I’m not sure where this leads, but I think we’ve seen over the last two or three weeks, at least since John Kelly’s press conference, that the adults in the room may be more like the president than we think. They might let us down.” Then, with the specter of the recent Niger incident in the air, and on the heels of the Afghanistan troop infusion, “they might in fact reflect the military in which they’re from, which is expeditionary.”

New low in U.S.-Russian Relations

Some of the worst U.S. foreign policy disasters since the end of the Cold War “are obvious,” said Ted Carpenter, TAC contributing editor and Cato defense and foreign policy scholar. Those include Iraq and Libya, Afghanistan and the loss of civil liberties at home due to the War on Terror. But the “worst disaster in the last 25 years will end up being be the deterioration in relations with Russia, because that can have some catastrophic consequences.”

“We are in a new Cold War,” he declared. “The blame for this is not all on one side. But I believe the United States and its allies deserve the vast majority of the blame, somewhere in the area of 80 percent.”

Expanding NATO eastward, reneging on implicit agreement not to expand – “they led the Russians to believe that NATO’s eastern border would be at the eastern end of Germany. That didn’t happen.” NATO intervention in Balkan charged the Russian suspicion and resentment, Carpenter. It intruded into what had been Russian spheres of influence.

But what about Vladimir Putin’s aggressive policies today? “Putin started off wanting to join the West,” pointed out former U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union Jack Matlock (1987-1991). One move after another, whether it be the West’s role in the economic collapse following the fall of Communism, NATO expansion, or the U.S. involvement in the so-called “color revolutions” in former Soviet countries, Russia began to foment serious resentment against its foundling American “ally.”

“Within Russia you get a nationalist upsurge which Putin has utilized,” Matlock pointed out. “He feels, as many of his people do, that Russia has been rejected, and has been rejected (by the West) in part, by American pressure. It’s difficult to ignore the role we play in this.”

Associate Professor of International Relations Robert English said the fixation on Putin is to partially scapegoat failures in both Republican and Democratic policies with Russia. “Bush pushed NATO right up to Russia’s borders and foolishly crossed a very clear red line in pushing the Western alliance towards Ukraine and Georgia … Obama “continued to push into Ukraine and continued expansion of NATO overall.” This after the “beloved” (President) Bill Clinton sparked expansion in the first place, he concluded.

But today’s Democratic narrative over Russian meddling in the election has overtaken the historical perspective. Today, Matlock points out, “we have put our president (Trump) in a position where if he does propose something (positive in relation to Russia) they will say, ‘oh, they must have something on him!”

“I don’t care if they have anything on him,” Matlock said. “I don’t see any credible reason for us to be enemies and I can see very powerful reasons to work together.”

And they must work together, as this is no longer a world of unipolar power – namely, the U.S. as the sole leader of the geopolitical chessboard–but a world of multi-polar politics with Russia, China and India ascending, said Paul Kennedy, professor of history and director of International Security Studies at Yale University.

In the final panel of the day, The Future of Great Power Politics, the author of The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers said we have to “get real” and think of the world in terms of these “four big guys.” No more does America have the fiscal endurance or the long term military capacity to be the world’s police.

“The unipolar moment is over,” he said. “The question is now, how do we manage that post-unipolar world?”

Cato Institute Vice President for Defense and Foreign Policy Studies Christopher Preble pointed out that smaller powers, even non-state actors, have been able to take advantage of new technology and weapons systems to make life miserable for the old guard, including the U.S. Nowhere is this more obvious than in our current wars. “The U.S. struggles to win, it struggles to win decisively.”

Michael Desch, professor of political science at Notre Dame University, noted the “Jacksonian moment” in terms of U.S. foreign policy might have some elements of traditional realism but is “a double edged sword” in that the surge of populism and pushback against Realpolitik are sending the Trump White House on a collision course with Iran.

John Mearsheimer, author and professor of political science at the University of Chicago, says “big power politics is back on the table” and that means realism is, too. But restraint may no longer be the partner of realism, as the U.S. pushes back against a rising China. But he warns that China, like all great powers, will expect the same privileges and liberties as the U.S. boasted when it, too, was a rising superpower.

“They’re going to project their power. You can expect more of that as time goes by. I don’t blame them a bit because this is how the world works,” he said. “If we have a Monroe Doctrine, don’t you think they will want their own Monroe Doctrine? Of course they are going to…This is nothing to do with Communism or Marxism, this is basic realpolitik. You want to be a real power, you want to dominate your region of the world.”

“Give us the debate”

In his opening remarks, Rep. Walter Jones (R-N.C.) lamented the lack of will and backbone from Congress on matters of war since 9/11. A longtime critic of the Iraq invasion and continuing war in Afghanistan, Jones told the story of a young woman he saw in the airport carrying a folded American flag in accordance with a servicemember or veteran who had died. “It was so sad for me,” he said, noting that any words he had for her seemed trite in comparison with her pain.

“Give us the debate,” he said, relating to decisions of war on Capitol Hill. He scowled at his colleagues’ lack of interest so far. “It’s like it doesn’t matter. I don’t understand that at all. We need to demand that the leadership of the House permit the Congress to debate war because if we don’t it’s going to be perpetual war from now on.”

“It’s time for the men and women of America to take back their constitution.”

(You can also watch the full video here and check the agenda below.)

Welcome

- Samuel Goldman, George Washington University

- Robert W. Merry, editor, The American Conservative

Opening Remarks

- Congressman Walter Jones, U.S. Representative for the 3rd District of North Carolina

The Fate of Realism and Restraint in the Trump Era

- Robert W. Merry, editor, The American Conservative

- William Ruger, Charles Koch Institute

- Mark Perry, contributing editor, The American Conservative

- Moderator: Kelley Vlahos, executive editor, The American Conservative

Who’s Responsible for the New Low in U.S.-Russia Relations?

- Ambassador Jack F. Matlock, Jr., former U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union

- Ted Galen Carpenter, contributing editor, The American Conservative

- Robert David English, University of Southern California

- Moderator: Scott McConnell, founding editor, The American Conservative

The Future of Great Power Politics

- John Mearsheimer, University of Chicago

- Paul Kennedy, Yale University

- Christopher Preble, Cato Institute

- Michael C. Desch, University of Notre Dame

- Moderator: Daniel McCarthy, Fund for American Studies