Reprinted with permission from Greg Mitchell’s newsletter Oppenheimer: From Hiroshima to Hollywood.

Three days until Hiroshima Day. Continuing my daily Countdown to Hiroshima over at my Pressing Issues blog, this time for August 3, 1945:

– On Tinian, Little Boy is ready to go, awaiting word on the weather, with General Curtis LeMay to make the call for takeoff. Mission starting on the night of August 5 appears most likely scenario. Hiroshima remains primary target, with detonation point the center of the city, not the military base or industrial heart.

– On board the ship Augusta steaming home for USA after Potsdam meeting, President Truman, Joint Chiefs chairman Admiral William Leahy, and Secretary of State James F. Byrnes – a strong A-bomb booster – enjoy some poker. Byrnes’ aide Walter Brown notes in his diary that “President, Leahy, JFB agreed Japan looking for peace. (Leahy had another report from Pacific.) President afraid they will sue for peace through Russia instead of some country like Sweden.”

Cillian Murphy rightly drawing raves, but J. Robert Oppenheimer has been portrayed in fictionalized film and TV dramas for more than 75 years, long before Christopher Nolan placed him at the center of his bio-pic thriller.

Renditions include actor Sam Waterston’s depiction in the seven-part Oppenheimer series in 1980 for PBS. Nine years later, Roland Joffe’s big-budget studio drama, Fat Man and Little Boy, foolishly cast the relatively unknown Dwight Shultz opposite megastar Paul Newman, who portrayed Gen. Leslie Groves, the Manhattan Project’s tyrannical military director. That same year, David Strathairn portrayed Oppenheimer in the TV movie Day One, and later in a PBS “American Experience” episode about the physicist’s security clearance ordeal, The Trials of J. Robert Oppenheimer.

In WGN’s little-watched 2014 series Manhattan (co-star Rachel Brosnahan had yet to become Mrs. Maisel), Oppenheimer was a fringe character, again played by an obscure actor, Daniel London. In the latest film, Nolan gives Oppenheimer star treatment via the charismatic Cillian Murphy. (Matt Damon plays Groves.) But what all of these wildly varying depictions and storylines have in common is this: Oppenheimer, who died in 1967, wasn’t around during their creation to advise, inform, or approve.

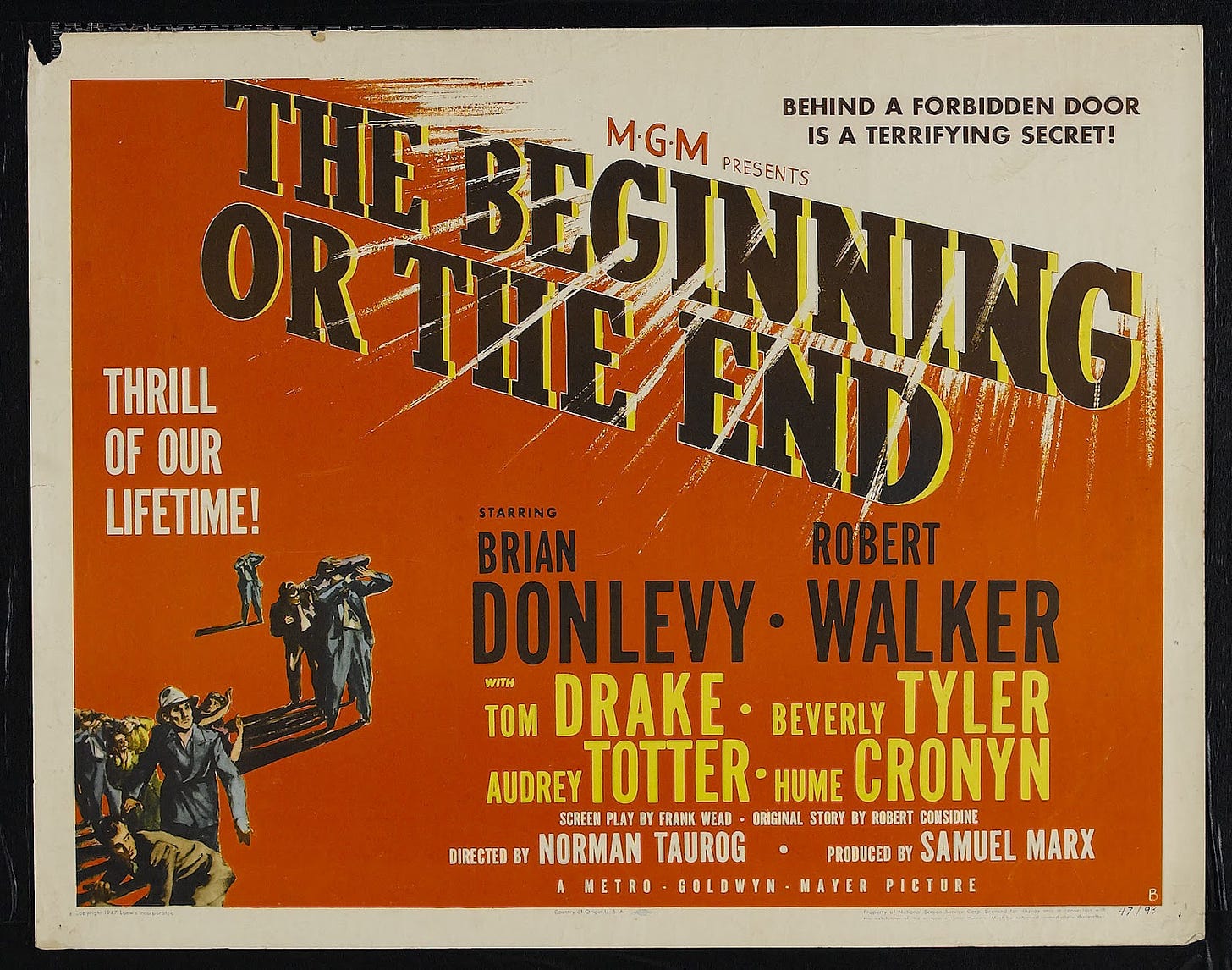

The producer of the one major docudrama that did appear during Oppenheimer’s lifetime – less than two years after the US detonated its atomic bombs over Japan – sought the physicist’s input and approval, and in that crucial role, “Oppie” succumbed to pressure. He regarded the script for MGM’s big-budget portrayal, The Beginning or the End, as poor, even laughable. Worse, it would be littered with dangerous falsehoods—thanks partly to White House and Pentagon demands—at a pivotal historical turning point, as US officials contemplated designing and testing more new weapons, including an H-bomb, that would set off an epic arms race with the Soviets.

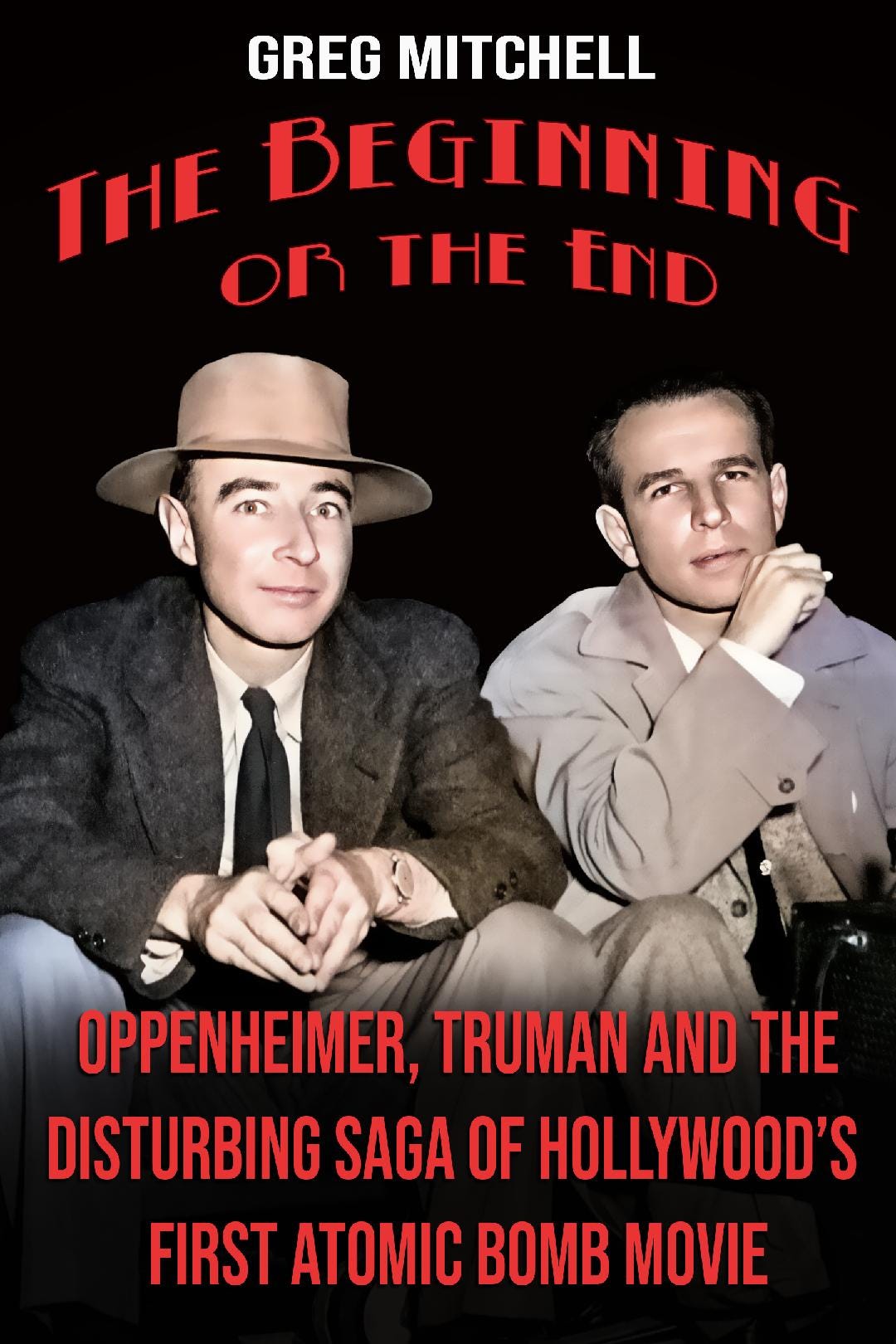

Oppenheimer, despite his concerns, ultimately agreed to be depicted as a key character and narrator. (He also sat for two interviews by Ayn Rand as she prepared the screenplay for a rival movie.) The making and unmaking of The Beginning or the End, a saga I explore fully in my 2020 book of the same title, reveals much—not only of Oppenheimer’s character, but what he faced as the target of relentless FBI bugging, tapping and other monitoring.

MGM began work on The Beginning or the End in the autumn of 1945, inspired by scientists begging Hollywood to produce a film that would discourage the government from building more powerful nukes that would imperil the world. Oddly, it was actress Donna Reed, through her husband, an agent, who got the project rolling after receiving two letters from a former high school chemistry teacher and Manhattan Project scientist.

As the film project progressed, studio co-founder Louis B. Mayer called it the “most important” movie he would ever produce. But in the year that followed, the intended message took a U-turn. Major – sometimes unintentionally comical – falsehoods were introduced into the script to such an extent that the final product would be little more than pro-bomb propaganda. President Harry S. Truman and Gen. Groves, both of whom were granted script approval, ordered dozens of cuts and revisions. Truman even forced a costly re-take and had the actor playing him fired.

More troubling for MGM executives, the studio needed to convince the scientists portrayed in the film to sign releases granting their permission for actors to portray them. Producers tried for months to get Albert Einstein, Leo Szilard, and Oppenheimer to sign off, while promising them (unlike Groves) no fee.

Einstein and Szilard eventually signed off, despite their qualms, but the ever-conflicted Oppenheimer resisted. Prepared for the worst, MGM changed his name in one version of the script to the implausibly WASP-y “Whittier.”

On April 18, 1946, producer Sam Marx sent Oppenheimer a copy of the latest screenplay in the hope he would at least “glance through it” before they met in Berkeley three days hence. That version had the Oppenheimer/Whittier character narrating and playing a central role in the film.

After dinner at Oppenheimer’s villa in the Berkeley Hills overlooking the San Francisco Bay, Oppie spoke frankly with Marx about the script, calling most of the supposedly real characters like himself “stiff and idiotic.”

Still, Oppenheimer told Nickson he found his Hollywood visitor “honestly eager to get the script improved,” but even after the promised revisions, he predicted, “It won’t be very good.”

At least in the current story, he added, the scientists were depicted as “ordinary decent guys, that they worried like hell about the bomb, that it presents a major issue of good and evil to the people of the world.” (In fact, Marx’s changes would be minor and the script only became more flaky, but Oppenheimer apparently never followed up.)

To portray Oppenheimer, the studio was set on the accomplished – though not A-list – Canadian actor, Hume Cronyn, who did not resemble him in the least.

Two weeks later, near the end of a lengthy phone conversation – the FBI had started tapping the home phone and recording the conversations – Kitty Oppenheimer informed her husband, who was away, that he’d received a letter from a “Hugh Cronin.” In the letter, which explained “why he would like to be you,” Kitty said (according to a FBI transcript, first revealed in my book), Cronyn gently mocked the script but promised to do his best in portraying Oppenheimer.

“Well, I’ll tell you what I did on this,” Oppenheimer replied, before making a reference to Gen. Groves’ top aide: “This very ugly creature, [Colonel W.A.] Consodine, called me and said that Marx had said it was all right and would I sign the release, and I said, sure. I got the release and I signed it with a paragraph written in saying that all of this is subject to my receipt of a statement from Mr. Sam Marx that he believes the changes that have been made are satisfactory.”

Kitty: Oh.

Robert: Well, I didn’t think there was anything else to do. I don’t want anything from them and if I can work on his conscience, that is the best angle I have. It just isn’t worth anything otherwise, darling.

The call faded in and out. “The FBI must have just hung up,” Oppenheimer quipped.

Kitty: Giggles.

“The only thing we can do there is to try to persuade them to do a decent job,” her husband concluded.

A few days later, Oppenheimer visited the set in Hollywood (see below) to meet Cronyn and view a rough cut of the film. His only recorded note was a complaint that the bomb was raised to the top of the tower at the Trinity test site far too fast.

As for Cronyn: Forty-three years later he would portray a man who strongly pushed Truman to use the bomb against Japan, Secretary of State James Byrnes.

Greg Mitchell is the author of a dozen books, including “Hiroshima in America,” and the recent award-winning The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood – and America – Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, and has directed three documentary films since 2021, including two for PBS (plus award-winning “Atomic Cover-up”). He has written widely about the atomic bomb and atomic bombings, and their aftermath, for over forty years. He writes often at Oppenheimer: From Hiroshima to Hollywood.