Reprinted with permission from Greg Mitchell’s newsletter Oppenheimer: From Hiroshima to Hollywood.

The letter addressed to Mrs. Donna Owen arrived at her oceanfront Santa Monica home on October 28, 1945. The return address on the envelope revealed that it came from her beloved high school chemistry teacher back in Denison, Iowa, when she lived on a farm and was still known as Donna Belle Mullenger. She had stayed in touch with handsome young Ed Tompkins for a few years after graduation, but then he suddenly vanished, without explanation, and had not responded to any of her letters.

This seemed odd. Tompkins (above with Donna and his fateful 1945 letter) had deeply influenced her outlook on life a decade earlier when she was an aimless sophomore, after he gifted her a copy of the popular Dale Carnegie self-help book How to Win Friends and Influence People. In short order her grades soared, she secured the lead role in the high school play (Ayn Rand’s The Night of January 16), and she was voted Campus Queen.

Donna Belle wanted to become a teacher but her parents could not afford a major school, so she moved to the West Coast to enroll in low-tuition Los Angeles City College. While she appeared in stage productions, she had no aspirations to become a professional actress. Soon the honey-haired beauty attracted the attention of talent scouts, leading to several screen tests. Signed by MGM to a seven-year contract at the age of twenty, she appeared in her first movie, The Get-Away, billed as Donna Adams.

Many supporting roles followed, with her name changed to one she hated, feeling it had a dull, harsh sound that didn’t reflect her personality at all: Donna Reed. Still, she secured minor roles and married her makeup man. She graduated from Mickey Rooney’s love interest in The Courtship of Andy Hardy to John Wayne’s object of desire in John Ford’s They Were Expendable. (Fearing she’d lose out if she took time off, she endured an abortion.) Along the way she became a popular girl-next-door pinup during World War II for homesick GIs. She got divorced and in June 1945, still only twenty-four-years-old, married her agent, Tony Owen.

Then, that autumn, she signed with RKO for perhaps her biggest role yet, as Mary Bailey, wife of James Stewart in Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life, after Ginger Rogers turned it down as “too bland.” At the same time she finally discovered what had happened to Ed Tompkins. A newspaper story revealed that he had been sworn to silence for several years after joining thousands of others in helping to create the first atomic bomb at the Manhattan Project site in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. After reading the article, she sent him another letter, this time care of Oak Ridge.

Now she had received a reply. Opening the envelope, she unfolded a typed, single-spaced, two-and-a-half-page letter from Dr. Tompkins. The tone, given their formerly close relationship, was surprisingly formal (despite its “Dear Donna” salutation), and urgent. “The development of atomic explosives necessitates a reevaluation of many of our previous modes of thought and life,” he began. “This conclusion had been reached by the research scientists who developed these powerful new explosives long before August 6, 1945.” That, of course, was the day the first atomic bomb exploded over the city of Hiroshima in Japan, killing more than 125,000, the vast majority of them women and children. Three days later, Nagasaki met the same fate, with a death toll reaching at least 75,000.

The day before Reed received the Tompkins letter at her modest beach house more than ninety thousand locals had gathered in the Los Angeles Coliseum to witness a “Tribute to Victory” program. It featured a re-creation of the bombing of Hiroshima, narrated by actor Edward G. Robinson. A B-29 bomber, caught in searchlights, dropped a package that produced a large noise and a small mushroom cloud. The crowd went wild.

Americans, weeks after the Japanese surrender, were relieved that the war was over but nervous about atomic energy. Scientists, political figures, and poets alike were sounding a similar theme – splitting the atom could bring wonderful advances, if used wisely, or destroy the world, if developed for military purposes. Atomic dreams, and nightmares, ran wild. “Seldom, if ever, has a war ended leaving the victors with such a sense of uncertainty and fear,” warned radio commentator Edward R. Murrow, with “survival not assured.”

In the rather dense letter to his former pupil, Tompkins explained that the scientists’ initial “excitement” and pride in what they had accomplished, under the leadership of J. Robert Oppenheimer, were now subsumed by much soul-searching. Until the Hiroshima blast, many of his colleagues were unaware they had been working on a munitions project. Others had signed physicist Leo Szilard’s futile petition asking President Harry S. Truman to hold off using the new weapon against Japan. (The petition was opposed by Oppenheimer.) In any case, a large number were now against the building of new and even bigger earth-shattering bombs.

Tompkins revealed that thousands of Manhattan Project scientists had now formed associations in Oak Ridge, Chicago, Los Alamos, and New York to deliver their warnings and “to foster thought and discussion which can lead to adoption of international control of atomic energy.” Contrary to claims by military leaders and politicians, there was “NO possibility” that the United States could keep a monopoly on production of these weapons. The so-called secret of the atomic bomb was known internationally. The Soviets, for example, would surely build their own bombs within a few years. Finally, there could never be an effective defense against these weapons, and “a hundred long-range rockets carrying atomic explosives could wipe out our civilization in a matter of minutes.”

In light of all this, it was imperative that effective international controls be established as soon as feasible, which Oppenheimer supported. But what did Donna’s old chem teacher (and positive thinking advocate) want her to do about it? Tompkins revealed that the new associations were showering elected officials in Washington with leaflets, lobbying influential reporters and commentators, and preparing a major book. This was “a good start but much remains to be done,” he noted. It seemed to him “there would be a large segment of the population that could be reached most effectively through the movies.” His final paragraph featured an explicit pitch:

Do you think a movie could be planned and produced to successfully impress upon the public the horrors of atomic warfare. . . . It would, of course, have to hold the interest of the public, and still not sacrifice the message. Would you be willing to help sell this idea to MGM? Or if not, could you send us the names of the men who should be contacted in this matter? We would be not only willing but anxious to offer our technical advice in the preparation of the script and settings. . . . You can, no doubt, think of many forms which such a picture could take.

Never inserting even a hint of personal familiarity from their days in Iowa, or asking about her life or career, Tompkins concluded with the plea, “Will you give the whole matter your consideration and perhaps discuss it with others at the studio? I’d appreciate hearing your reaction to the suggestion as soon as possible.”

Just days later, after speaking to other members of the activist group at Oak Ridge, Tompkins fired off a second letter to “Mr. and Mrs. Tony Owen.” Tompkins boldly proposed that the couple fly east to Oak Ridge at their own expense the following week to discuss the project, with no time to waste. Together they could hash out a scenario for “a very good picture with a lot of public appeal” that would hit the theaters before any other entry – and then catch a short flight to Washington to gain the required approval of the Manhattan Project director, General Leslie R. Groves (with Donna below) . “I wish to thank you for the great interest you have taken in this matter,” Tompkins concluded.

Well, that was a lot for Donna Reed, or anyone, to digest. Just seven years earlier the same man had been delivering quite a different lesson in a classroom. Fortunately she had someone to share it with and, as she told Tompkins in a brief phone call, carry the ball in responding to his feverish pleading. This was her new husband, Tony Owen, a slick, fast-talking dynamo who was thirteen years her senior. Following a stint in the military, he settled in Los Angeles and secured his first clients as a talent agent.

When he finished reading the Tompkins missives, Owen started calling producers to gauge their interest, if any. Having not heard from Donna again, Tompkins called her at home. She said she had started three letters to him but each became outdated by events. Her husband had learned from studio insiders that it might be a simple matter to get such a movie produced if the military signaled its approval – and exclusive dramatic rights for key figures in the story could be obtained. Reed warned Tompkins, however, that Hollywood studios were reluctant to make any pictures with “political repercussions.” When he told her that scientists were already sketching scenarios for a script, she advised that surely any of them would be “completely rewritten” by the studio.

Tony Owen, meanwhile, called his friend Samuel Marx, a top producer at MGM, where Reed was still under contract. Marx agreed to meet him the next day for breakfast at the swanky Beverly Wilshire Hotel. There he would find Owen in a highly animated state. Owen showed him the letter to his wife from Tompkins, which the producer found fascinating. (Marx got the impression that Tompkins may have once had something of a secret “crush” on his pupil.) The producer offered to take Owen to meet with Louis B. Mayer, one of the most powerful men in town and the studio chief since the 1920s, straight away. So they raced their automobiles to the studio lot at Culver City.

As it happens, MGM had expressed some interest in an atomic bomb film nearly two months earlier, with the Japanese victims of the attacks still smoldering in the ruins. On August 9, just hours after the assault on Nagasaki, MGM’s Washington representative, Carter Barron, phoned the chief of the Pentagon’s Feature Film Division to discuss the possibility of the studio rushing ahead with an exclusive movie about the bomb project.

Now, MGM was being handed, via Donna Reed and Ed Tompkins, a unique and exclusive entry point to an ambitious cinematic bomb project. To date the studio’s main reference to the new weapon was crowning its newly signed starlet Linda Christian “The Anatomic Bomb” (leading to a full-page photo of her in a swimsuit in Life magazine).

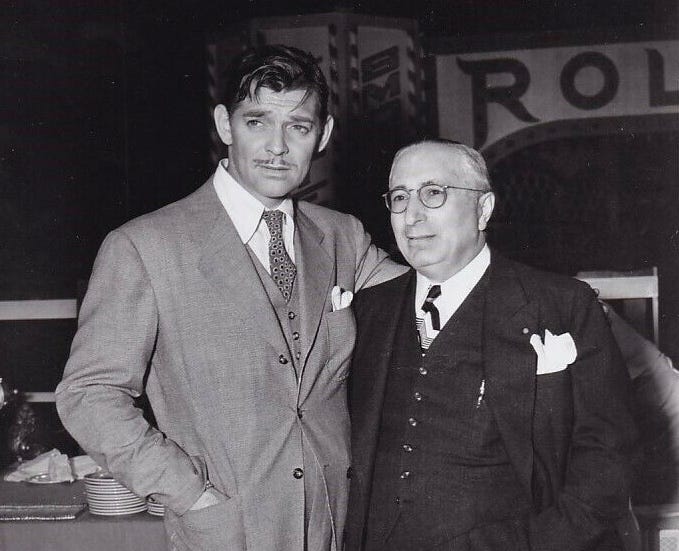

In his massive office at the studio, sitting behind his pure-white oval desk in the sprawling Thalberg Building, L.B. Mayer (with Clark Gable, above) greeted the fervent Marx and Owen. The actress Helen Hayes once called Mayer “the most evil man I have ever dealt with in my life,” yet called MGM “the great film studio of the world – not just of America, or of Hollywood, but of the world.”

Listening to the atomic bomb pitch, Mayer grew excited. With little prompting, he promised that if the necessary approvals and rights were gathered he would make an epic film on this subject his top priority for 1946. He would budget at least $2 million for it, a lofty sum for that time. It might one day be “the most important movie” he would ever film (and this was the man who had made Gone with the Wind), perhaps in the vein of his 1943 film, Madame Curie, but more topical.

Eager to rush forward, Mayer urged Owen and Marx to seek clearances that very minute, straight from the top – “from the horse’s mouth,” as Mayer put it. “Let’s call President Truman himself,” he suggested. Mayer was a rock-ribbed Republican, but the studio titan believed Truman would surely accept his call. It took some persuading, but Owen finally talked him down from that idea. Instead, Mayer ordered Marx to call the studio’s representative in DC, Carter Barron, to find out if White House and military approvals were likely to come. Another key target: J. Robert Oppenheimer.

MGM would soon order the writing of a script and the movie went into full production. Over the course of the next year, however, the original conception – a critique of the atomic attacks on Japan and warnings about any future nuclear buildup – would be eliminated after intervention by President Truman and General Groves, as the film was transformed into blatant, sometimes laughable, pro-Bomb propaganda. Robert Oppenheimer, nevertheless, would accept the script, which was filled with falsifications, and agreed to be portrayed in the movie at its center.

»»>The above excerpted from my award-winning recent book The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood – and America – Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.

Thanks for reading Oppenheimer: From Hiroshima to Hollywood! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Greg Mitchell is the author of a dozen books, including “Hiroshima in America,” and the recent award-winning The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood – and America – Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, and has directed three documentary films since 2021, including two for PBS (plus award-winning “Atomic Cover-up”). He has written widely about the atomic bomb and atomic bombings, and their aftermath, for over forty years. He writes often at Oppenheimer: From Hiroshima to Hollywood.