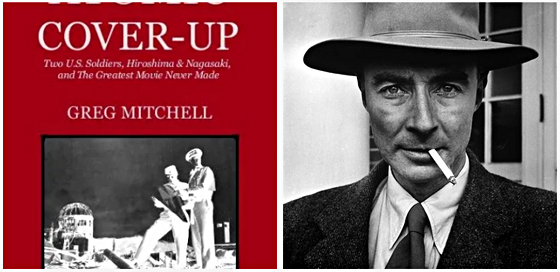

Reprinted with permission from Greg Mitchell’s newsletter Oppenheimer: From Hiroshima to Hollywood.

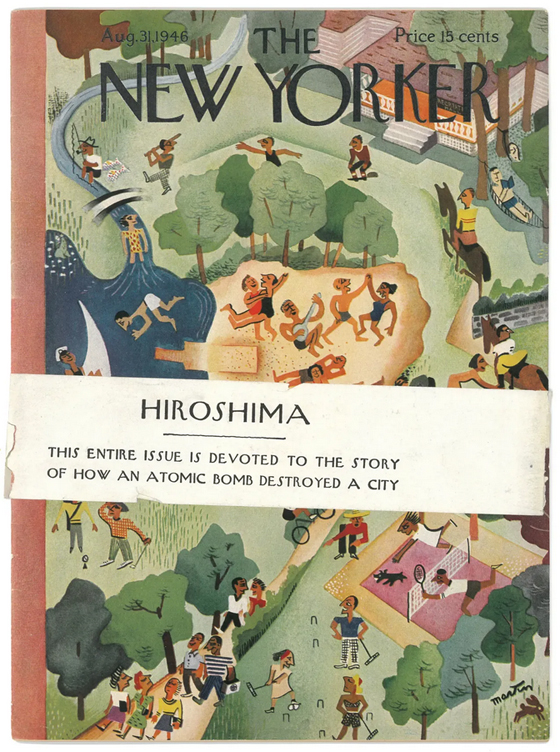

Earlier this week, we looked at the genesis of John Hersey’s famous “Hiroshima” article for The New Yorker (which appeared 77 years ago this week) and book. Now here is the response to the landmark piece, including criticism that it did not go far enough, adapted from my recent book The Beginning or the End.

Columnists and editors, most of whom had expressed strong support for the use of the bomb, nevertheless praised the massive Hersey article, many calling it the strongest reporting of its time. The New York Times declared that every American “who has permitted himself to make jokes about atom bombs, or who has come to regard them as just one sensational development that can now be accepted as part of civilization . . . ought to read Mr. Hersey.” The editorial reminded readers that the “disasters at Hiroshima and Nagasaki were our handiwork,” and that the crucial argument that the bomb reputedly saved more lives than it took might appear unsound after reading Hersey.

On top of that, Hersey chronicled the gruesomely unique way so many perished in death-by-radiation, which caused at least 20 percent of the casualties. Writing to New Yorker editors, the journalist Janet Flanner compared the article to Matthew Brady’s photographs during the Civil War, one of the first “records of how people really looked in war.”

Some readers felt this grim account of six of the first atomic bomb survivors was somewhat diminished by its surroundings in the upscale magazine – the usual ads for quality booze, Tiffany pins, leg cosmetics, and vacations abroad. A flood of letters to The New Yorker, however, revealed that most readers were terribly moved. A college student wrote, “I had never thought of the people in the bombed cities as individuals.” Many mentioned that they were now ashamed of what America had done.

A young scientist, once proud of his work for the Manhattan Project, revealed that he wept as he read the article and was “filled with shame to recall the whoopee spirit” with which he and others had received the news of the bombing, recalling a “champagne dinner” that night. “We didn’t realize” the horror and human effects, he added. “I wonder if we do yet.” (This could be written today – after Oppenheimer.)

One reader not pleased was Henry Luce, Hersey’s main employer. Time claimed that Hersey “had practically stumbled into” this story and that New Yorker editor Harold Ross (“a man given to juvenile and profane tantrums”) had only printed the article at that length in one issue because he was notably short of good material.

The novelist Thomas Mann had an interesting take himself. He hailed the article but declared it should not be translated for the postwar Germans because it is “their only pleasure to enjoy the mistakes and sins committed anywhere else in the world.”

Would “Hiroshima” provoke a public rethinking of the wisdom of Truman’s decision to use the bomb? To date that debate had centered on what to do with the next bombs, not what had been done with the first ones. Atomic scientists who had never before addressed the divisive Hiroshima decision – the new Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists had just called it “water over the dam” – were now speaking out. Albert Einstein commented that the bomb probably was used primarily to end the Pacific war before Russia got into it. (J. Robert Oppenheimer, on the other hand, remained silent.)

Not everyone responded positively. “I read Hersey’s report,” one subscriber wrote The New Yorker. “It was marvelous. Now let us drop a handful [of atomic bombs] on Moscow.” General Thomas Farrell was so angry he asked Bernard Baruch to propose another article to the editors at the magazine – about six POWs mistreated by the Japanese and how they felt about the bomb. (That American POWs died in the Hiroshima attack would remain a secret for decades.)

Others felt Hersey had not gone far enough. The writer himself admitted to publisher Alfred A. Knopf that he had “been at great pains to keep the tone of guilt about using the bomb at a minimum.” The New York Times, in a second “minority opinion” editorial, charged that Hersey had merely “given us a picture of war’s horrors as the world has long known them, rather than a picture of the unprecedented horrors of atomic warfare.” The simple number 100,000 – indicating the number killed in one day – conveyed more about the meaning of Hiroshima than any evocative anecdote.

The left-wing critic Dwight Macdonald was more caustic. Macdonald despised the article’s “suave, toned-down, underplayed kind of naturalism,” its “moral deficiency” in vision, its “antiseptic” prose. Naturalism, he suggested, was no longer adequate “either esthetically or morally, to cope with the modern horrors.”

The writer Mary McCarthy mocked The New Yorker for declaring a moral “emergency” while surrounding the Hersey article with all those cigarette and perfume ads. While agreeing that the atomic bomb threatened the continuity of life, she unfairly characterized the key survivors in the Hersey article as “busy little Methodists.” Hersey, she asserted, minimized the atomic bomb “by treating it as though it belonged to the familiar order of catastrophes. . . . The existence of any survivors is an irrelevancy, and the interview with the survivors is an insipid falsification of the truth of atom warfare. To have done the atom bomb justice, Mr. Hersey would have had to interview the dead.”

But it was Saturday Review editor Norman Cousins whose reaction would end up having the most impact. He had already argued that the bomb might have been aimed at the Russians as much as the Japanese. Now in an editorial titled “The Literacy of Survival,” he asserted that Americans, despite Hersey’s achievement, still did not fully comprehend what they had done.

Have we as a people any sense of responsibility for the crime of Hiroshima and Nagasaki? Have we attempted to press our leaders for an answer concerning their refusal to heed the pleas of the scientists against the use of the bomb without a demonstration?

He concluded by calling for a national “moratorium” on all normal habits and routine, “in order to acquire a basic literacy” on the moral implications of the atomic bombings and the atomic age. If this accomplished little it would at least “enable the American people to recognize a crisis when they see one and are in one.”

What this editorial, along with the Hersey article (his book derived from the article was still being rushed to press), would accomplish more than anything, unfortunately, was to inspire pro-bomb authorities, from Harvard president James Conant to Truman’s Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson, to take redemptive action, involving a quite different major article in another leading magazine, to reinforce the Hiroshima narrative they had promoted from the start. We will turn to that disturbing, highly influential – to this day – saga next, along with President Truman’s response to the Hersey piece.

Thanks for reading Oppenheimer: From Hiroshima to Hollywood! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Greg Mitchell is the author of a dozen books, including “Hiroshima in America,” and the recent award-winning The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood – and America – Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, and has directed three documentary films since 2021, including two for PBS (plus award-winning “Atomic Cover-up”). He has written widely about the atomic bomb and atomic bombings, and their aftermath, for over forty years. He writes often at Oppenheimer: From Hiroshima to Hollywood.