Reprinted with permission from Greg Mitchell’s newsletter Oppenheimer: From Hiroshima to Hollywood.

In late-October 1946, a near-final version of the first Hollywood drama depicting the creation and use of the atomic bomb was screened for an elite audience at the Naval Building auditorium in Washington, D.C., including leading journalists and top aides to President Harry S. Truman. This was the MGM film, The Beginning or the End. Truman had ordered the deployment of two atomic bombs over the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, killing at least 200,000, a little more than a year earlier.

The screening came at a sensitive point, amid the sensational response to John Hersey’s article in the New Yorker near the end of that summer (see my post yesterday). Truman’s approval rating in the Gallup Poll, which stood at 82% at the close of the war, had plunged to little more than half of that. So the MGM film was viewed as a possible major factor in aiding, or harming, the future popularity of Truman, and further development of the bomb.

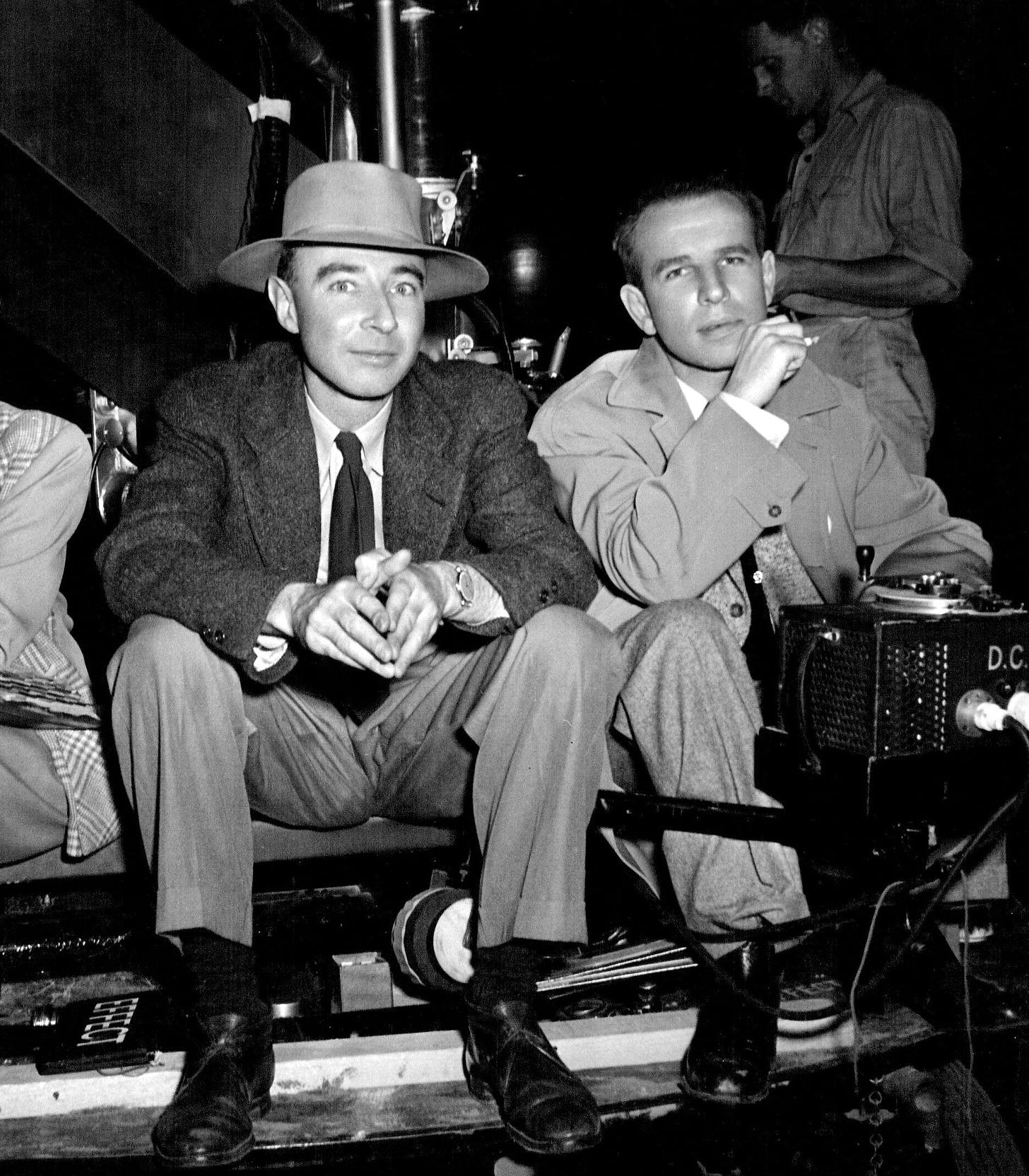

The heavily revised film, which starred Brian Donlevy (as Gen. Leslie R. Groves) and Hume Cronyn (as J. Robert Oppenheimer), no longer contained a single reference to Nagasaki, and now underscored the official pro-bomb narrative in scene after scene. In this view, only the use of the bomb against the two Japanese cities prevented a U.S. invasion that would have cost up to half a million American lives. The audience at the Naval Building broke in with applause at several key moments when decisions, however melodramatic, were made to build or use the bomb.

But trouble brewed. Walter Lippmann, the country’s most influential newspaper columnist, considered the film little more than a banal and typical “American success story,” he wrote to a friend, and couldn’t believe so many eminent scientists had given their approval. That letter was forwarded to Oppenheimer, who had directed the creation of the scientists at Los Alamos, and had signed a released allowing his portrayal in MGM movie, despite finding much of it “idiotic.”

More importantly, President Truman’s aides felt uncomfortable about one key sequence, and Lippmann found the same scene “shocking.”

Charles Ross, his press secretary, informed MGM on October 29 that everyone “enjoyed very much” the screening. “This is a thrilling picture,” he added. “The story is beautifully worked out, and the acting is fine.” The only problem was: “something needs to be done about the sequence in which President Truman appears.” He didn’t need to spell this out in the letter – he had already discussed the problem with the MGM executive in charge of the picture, James K. McGuinness, at the screening.

Ross, after discussing the matter with Truman, had scrawled “rejected” across the top of the relevant two pages of the script which had been sent to him for approval, which I discovered at the Truman Library in researching my book on the movie. In other words, the White House held the right of script approval or veto.

The scene pictured Groves and Stimson informing Truman (played by veteran character actor Roman Bohnen) at the White House about the existence of the bomb project after President Roosevelt’s death in April 1945. Truman is surprised to learn this and is a bit concerned: “Two billion dollars to date, that’s a hot potato.” The segment was larded with outrageous untruths, even after all that vetting by scientists and military experts – such as Groves telling Truman that “there is reason to believe” that the Japanese would “be meeting our invasion ships and troops with atomic weapons.” Groves then projects U.S. troop losses in any invasion of Japan at “half a million men,” at a minimum.

Truman, who has been gazing out the window at the Washington Monument, now looks at a picture of FDR on his desk and says, “President Roosevelt must have given this a great deal of thought – and what it may mean in the future.”

But none of that displeased Truman, Ross and Lippmann. They objected to the celluloid President announcing to his visitors, without much reflection – after all, he’d just learned that the weapon even existed – that the U.S. would certainly use the weapon against Japan when it was ready, because “I think more of our American boys than I do of all our enemies… We will tell Japan to surrender or face destruction. If they refuse you will take it to the [U.S. base in the] Mariannas and use it.”

Lippmann, hoping to get that scene changed or cut, had told his friends that it would “disgrace” Truman and America. It reduced the role of the President “to extreme triviality in a great matter,” Lippmann wrote in his letter. “Serious people abroad are bound to say that if that is the way we made that kind of decision, we are not to be trusted with such a powerful weapon.”

Taking a wider view, Lippmann expressed outrage that the “basic theme of the film is not the problem of the atomic bomb in the world, but the success story the Americans, particularly General Groves, in making the bomb.” The multiple romance angles in the movie threatened to reduce the drama to absurdity. And Stimson, he complained, was pictured “as a doddering old man.” Lippmann was amazed that since the film was such a “great disservice” to the famed scientists he was “surprised that they have permitted it.” (Again: Oppenheimer still signed off on the script, as I wrote here awhile back).

In sum, “The thing should not have been done at all or, if done, it should have been a documentary film with a purely educational purpose.”

After receiving the complaint from the White House about the scene with Truman vowing to drop the bomb, John K. McGuiness, a political conservative best known for writing the story for the Marx Brothers’ A Night at the Opera, tossed out the offending scene and wrote a new one, within two days. He rushed three copies to Charles Ross, who was staying with Truman in Kansas City, and even offered to fly there to discuss it. He informed Ross in the November 1 cover letter that he had incorporated “all the matters we talked about” and not only that – he was “eager” to “incorporate anything else you deem advisable,” even though MGM was now pressed for time.

“Craven” is not too strong a word this.

McGuinness informed Walter Lippmann about the changes, claiming to be “deeply impressed by your feeling that we were showing our country’s Chief Executive deciding a monumental matter in what was a much too-hasty fashion.” Lippmann, in turn, assured a top adviser on the bomb project that the crisis had passed, observing whimsically that “sufficiently drastic criticism does have it effect upon the producers.”

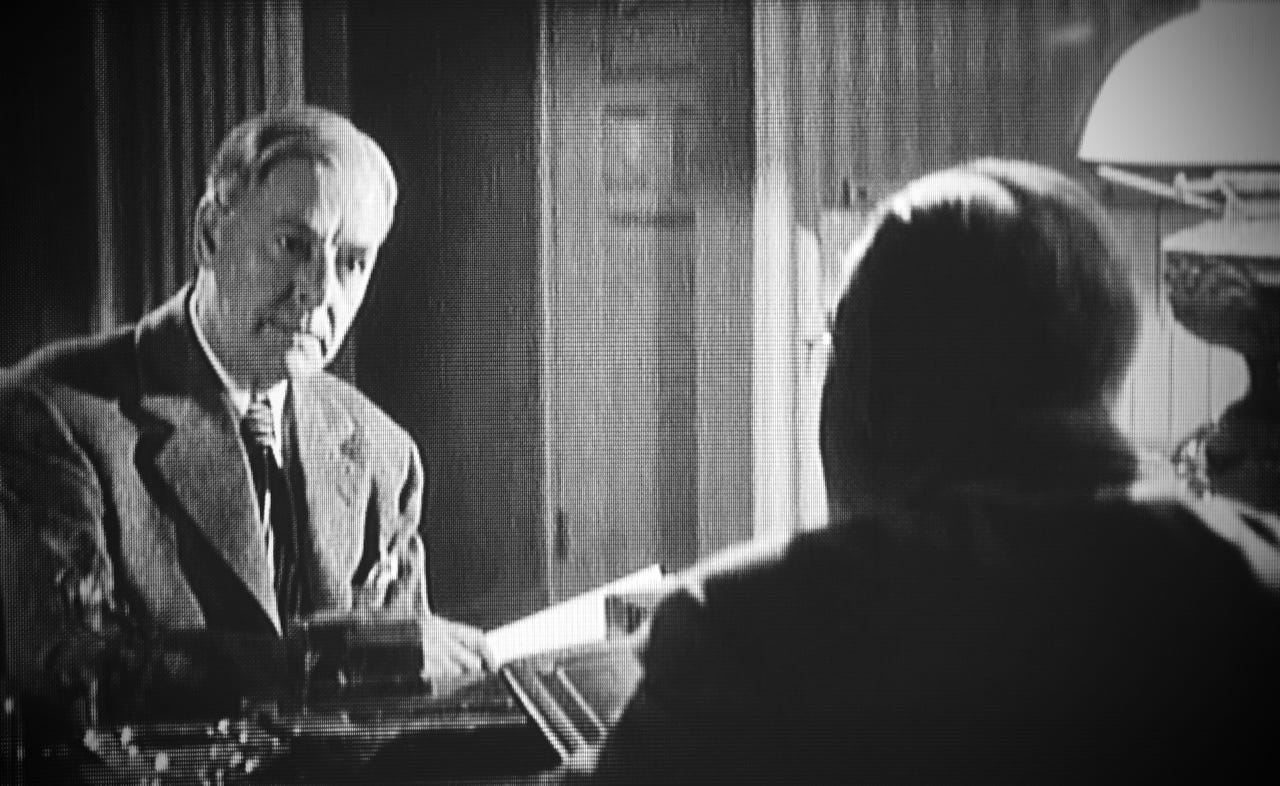

The new scene placed Truman in Germany, talking to Charles Ross across a desk just after his secretary had handed out copies of the Potsdam Declaration, which called for Japan’s unconditional surrender, to the press in July 1945. The script directions now declared, “it must be emphasized that the President is a man of upright and military bearing; that he is physically trim, alive and alert, and that his actions are brisk and certain.”

Filmed from the rear (as the President had demanded) in a darkened room, Truman’s faceless authority seems almost God-like. Ross informs him that some in the press were curious about that line in the declaration promising that Japan faced “prompt” destruction. Some of the reporters “think we’ve got some sort of mysterious new weapon.” Truman replies: “Those newspapermen are shrewd guessers.”

Then he finally reveals to Ross the “top secret” shocker: “Our country, with the help of scientists from nearly all the United Nations, has developed the most fearful weapon ever forged by man – an atomic bomb…It has been tested and it works.” Its destructive power was almost beyond imagining, but in peace “it will provide such power as will eventually lift most of mankind’s burden.”

Ross responds by exclaiming that if the Japanese had it, “they would surely use it on us.”

“That’s a persuasive argument, Charlie – but not a decisive one,” Truman calmly replies. The President explains that in consultations “every day for weeks now” with top military leaders, British leader Winston Churchill and “our greatest scientists,” the “consensus of opinion is that the bomb will shorten the war by approximately a year.” (In reality, few imagined that surrounded, starving, Japan would hold out for even half that time, and might even surrender quickly after the Soviets, as planned, attacked them in August 1945.)

Ross wonders if anyone disagreed. The President answers: “Nobody, actually. Some scientists who worked on the project think we should drop it on an uninhabited area as a warning. But the staff is sure the Japanese militarists would never let their people learn about it.”

“I go along with this completely,” Ross affirms.

Ross sympathizes with Truman about the difficulty of his decision. “You must have spent many sleepless nights over it,” Ross says. Truman replies: “Yes, it has cost me some sleep. I have had to make a tremendous decision.” The scene in this version of the script concludes with this exchange:

The President: The army has selected certain Japanese cities which are prime military targets – because of war industries, military installations, troop concentrations or fortifications. We will shower them for ten days with leaflets telling the populations to leave – telling them what is coming. We hope the warnings will save lives.

Ross: They should save plenty of American lives, too.

The President: A year less of war will mean life for untold numbers of Russians, of Chinese – of Japanese – and from three hundred thousand to half a million of America’s finest youth. That was the decisive consideration in my consent.

Ross: As President of the United States, sir, you could make no other decision.

The President: As President, I could not. So I have instructed the Army to take the bomb to the Marianas and – when they get the green light – to use it.

As drama this sequence, I suppose, succeeds but one can fault it on several factual grounds. Military considerations, for example, were not paramount in the targeting decision – we mainly wished to hit cities that had not already been heavily bombed to judge the effects of the blast – and it vastly inflated the number of likely American lives saved. And there was no showering of leaflets in warning of an attack in advance, let alone for “ten days.”

On November 8, Ross told McGuinness that it was “a pleasure to work with you,” but still requested further changes. “Enclosed is the revised script,” Ross wrote. “You will notice that I did not make very many changes. It was a pleasure to work with you and I trust that everything will turn out satisfactorily.” That was fine with MGM, little more than a Pravda-like mouthpiece now. (Much more in my book.)

In the final draft, besides some minor changes in wording, the already-inflated length of time the bomb would shorten the war increased from “approximately a year” to “at least a year.” The reference to scientists calling for a demonstration shot was deleted entirely (poor poor pitiful Szilard). Ross was given this new line: “Thank God we’ve got the bomb and not the Japanese!” Added was a flowery Truman quote, predicting that in peacetime “atomic energy can be used to bring about a golden age – such an age of prosperity and well-being as the world has never known.”

Another revealing revision: In a cagey move, the president no longer responds when Ross suggests that he must have spent many a sleepless night wrestling with the decision. Now Truman simply does not reply. So the sleepless nights idea is introduced but Truman will be free to deny it later in real life (as he would, as we’ve seen, more than once). MGM had tried to introduce the concept of a morally conflicted Truman, which he then thoroughly expunged.

On November 18, as producer Sam Marx frantically ordered more re-takes, McGuinness thanked Ross for his latest corrections, and assured him that “it will be done exactly as it has been revised unless we find that either of the actors has difficulty reading a word here or there.” In fact, as we’ll see tomorrow, the actor playing Truman would be fired.

When Vannevar Bush visited the White House to confirm that Truman had, indeed, endorsed the latest changes, Charles Ross assured him that he had not engaged in any kind of “censorship.” He had merely tried to guarantee, Bush would report, “that the President was properly presented… and that the historical account was reasonably accurate.”

Tomorrow: The fired actor writes a very sly note to Truman.

Just published: an expanded edition of my book Atomic Cover-up, now with several thousand words of mine re: Oppenheimer. And it’s on sale this week as an ebook for just $3.99 ($12.95 for the paperback).

Thanks for reading Oppenheimer: From Hiroshima to Hollywood! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Greg Mitchell is the author of a dozen books, including “Hiroshima in America,” and the recent award-winning The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood – and America – Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, and has directed three documentary films since 2021, including two for PBS (plus award-winning “Atomic Cover-up”). He has written widely about the atomic bomb and atomic bombings, and their aftermath, for over forty years. He writes often at Oppenheimer: From Hiroshima to Hollywood.