Reprinted with permission from Greg Mitchell’s newsletter Oppenheimer: From Hiroshima to Hollywood.

This happened a few decades ago, but needs little updating today.

Approaching Hiroshima from the east on the bullet train from Tokyo, one can’t help feeling a certain morbid fascination along with considerable dread. After all, if it’s your first trip, you have never before set foot in a city completely destroyed by a single bomb that also spread radioactive debris over a wide area. On top of that, if you are an American, it was your country that did it.

Like others in my party, I had laughed and joked along the way, between attempts at fast-speed sightseeing. On a drizzly July day, Mt. Fuji was obscured by clouds and the view of Kyoto from the train platform was similarly murky. Unlike my fellow journalists, I’d seen Fuji and Kyoto before, during a 1976 trip, so I shook off the disappointment to concentrate on the unnerving notion of entering Hiroshima, as we hurtled west, finally in the bright sunshine of mid-afternoon.

One thing was certain: I was as ready for this two-week visit (extremely lengthy for a foreign journalist or historian) as I would ever be, after a five-day immersion in Tokyo. We had interviewed a wide range of nuclear experts, sociologists, bomb survivors. On a positive note, a physician revealed that, contrary to popular belief, genetic mutations and health defects in the children of those exposed to the bomb were minimal or unproven, although evidence to the contrary could appear at any time (causing considerable anxiety in these families). Years ago, members of the second generation, or nisei, had trouble finding mates, as would-be marriage partners feared they might produce defective children. This was what I had come to Japan to find: the first of what would soon be a stream of hidden truths about the bomb.

Heading for Hiroshima on the super-express train from Tokyo the congested city appeared through a verdant valley as the train hurtled in and out of tunnels. Even at a distance I couldn’t help gazing at the sky and imagining an unearthly explosion over the city or a billowing mushroom cloud.

From the train station, Hiroshima seemed like any other large, modem Japanese city. As we’d been warned, it was hot as hell. Our hotel was within walking distance of ground zero, the Peace Park and Peace Museum, but from my window it could have been Austin or Seattle. Fortunately, one of the young English-speaking aides from the foundation sponsoring this trip offered to drive me to the top of Hijiyama for a bird’s-eye view.

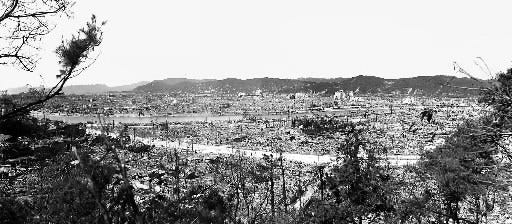

Hijiyama is a sacred hill that thousands climbed after the bombing, seeking escape from the cauldron of smoke and flames below. Finding relief too late, thousands died here and their bodies were still being found months later. One of the most affecting passages in the pivotal book Death in Life by my friend and co-author, Robert Jay Lifton, was the account of a Japanese history professor, who recalled climbing the hill on the day of the bomb and then looking back to find that Hiroshima had “disappeared … Of course I saw many dreadful scenes after that but that experience, looking down and finding nothing left of Hiroshima, was so shocking that I simply can’t express what I felt…. Hiroshima just didn’t exist.”

Now, from Hijiyama, one could observe a thriving city of nearly 800,000, triple its 1945 size (but known elsewhere in Japan as something of a “country” town beloved for its oysters). From Hijiyama, it was easy to conjure the pre-bomb Hiroshima, for the topography is the one thing that was not utterly altered on August 6, 1945. Cutting through the city, the tributaries of the Ota River reach for the sea like seven fingers of a giant hand. It was in these waters that thousands sought safety on that day, only to boil and float away, some to that sea.

From above one can fully appreciate how Hiroshima sits in the bottom of a bowl, surrounded by hills on three sides. These hills provided what the U.S. targeting committee in 1945 called a unique “focusing” effect that might turn the initial force of the atomic blast right back on the city (Robert Oppenheimer did not object). This was not seen as a moral liability but a desirable bonus that would kill and destroy even more effectively.

When it was over, President Truman, in his speech to the nation, would nevertheless describe Hiroshima, where 85% of the casualties were civilians, simply as “a military base.”

Looking out from Hijiyama a visitor today can hardly fail to envision a weapon of mass destruction exploding in a bright flash high over the center of the bowl. It is one thing to read about this, to try to imagine it, but quite another to actually “see” it: an apocalyptic blast, directly and deliberately (that’s the thing) over a large, sprawling city, targeting every citizen for annihilation, with radioactive fallout and “black rain” to follow.

This was another truth well worth a trip across the ocean. If only there were film footage of that moment on August 6, 1945, from this vantage point nuclear weapons might be history.

My visit to Hijiyama remains vivid in my memory today, decades later. It has, one might say, sparked and renewed my three books, hundreds of articles, thousands of blog posts, and one documentary film ever since.

Hiroshima from Hijiyama, then and now:

Just published: an expanded edition of my book Atomic Cover-up, now with several thousand words of mine re: the movie and the man Oppenheimer. And it’s on sale this week as an ebook for just $3.99 ($12.95 for the paperback).

Thanks for reading Oppenheimer: From Hiroshima to Hollywood! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Greg Mitchell is the author of a dozen books, including “Hiroshima in America,” and the recent award-winning The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood – and America – Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, and has directed three documentary films since 2021, including two for PBS (plus award-winning “Atomic Cover-up”). He has written widely about the atomic bomb and atomic bombings, and their aftermath, for over forty years. He writes often at Oppenheimer: From Hiroshima to Hollywood.