Reprinted with permission from Greg Mitchell’s newsletter Oppenheimer: From Hiroshima to Hollywood.

My photo, above, on another August 6, out on a branch of the Ota River, where thousands died, seeking relief.

In the movie Oppenheimer the scientists at Los Alamos, as I observed yesterday, learn that their new weapon had exploded over a Japanese city when it is broadcast over a public address system. Almost at the same time, the physicist who directed the bomb project there receives a phone call from Gen. Leslie R. Groves, informing him that the first bomb had gone off with quite a “bang.” These messages arrive suddenly, out of thin air, on August 6, 1945, and appear rather informal.

On the other hand, the official announcement for press and public had been carefully prepared and revised continually for several weeks.

President Truman, who had approved the attack on Japan, which doomed at least 125,000 to death, faced the task of telling the American press and public two shocking and astounding developments: the existence of a revolutionary new weapon, and that American forces had exploded this device of extraordinary destructive power over a Japanese target.

It was vital that this event be understood as a triumph of military power and at the same time consistent with American decency and concern for life. Everyone involved in preparing the presidential statement over the past weeks – including Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson and Gen. Leslie Groves, director of the Manhattan Project – knew that the stakes were high, for this marked the creation of the official narrative of Hiroshima, which still holds sway today.

When this shocking news emerged that morning seventy-eight years ago, President Truman was at sea, returning from the Potsdam conference, so the announcement took the form of a press release, a little more than a thousand words long. Shortly before eleven o’clock in the East, an officer from the War Department arrived at the White House bearing bundles of publicity releases. Assistant press secretary Eben Ayers shortly read the president’s announcement to about a dozen members of the Washington press corps.

The statement was so momentous, and the atmosphere so casual, the reporters had trouble grasping it. “The thing didn’t penetrate with most of them,” Ayers later recalled. At least one reporter who rushed to call his editor found a disbeliever at the other end of the line.

And no wonder. The first sentence set the tone: “Sixteen hours ago an American airplane dropped one bomb on Hiroshima, an important Japanese Army base. That bomb had more power than 20,000 tons of TNT. …The Japanese began the war from the air at Pearl Harbor. They have been repaid many fold. …It is an atomic bomb. It is a harnessing of the basic power of the universe.”

Truman’s four-page statement had been crafted with considerable care over many weeks, although the target city had been left blank. From its very first words, however, the official narrative was built on a lie: Hiroshima was not an “army base” but a city of 350,000. It did contain one important military encampment and staging area, but the bomb had been aimed at the very center of a city (and also far from its industrial area). It aimed to take advantage of what those who picked the target called the special “focusing effect” provided by the hills which surrounded the city on three sides. This would allow the blast to bounce back on the city, destroying more of it, and its citizens.

More than 15,000 military personnel lost their lives in the bomb but the vast majority of the dead in Hiroshima would be women and children. Also: at least a dozen American POWs. (When Nagasaki was A-bombed three days later it was officially described as a “naval base” yet less than 200 of the 100,000 dead were military.)

There was something else quite vital missing in Truman’s announcement: Because the president in his statement failed to mention radiation effects, which officials knew were horrendous, the imagery of just a bigger bomb would prevail in the press. Truman described the new weapon as “revolutionary” but only in regard to the destruction it could cause, failing to mention its most lethal new feature: radiation.

At the same time, no one but top American officials and generals knew that the Soviet Union was just hours from declaring war on Japan. “Fini Japs” when that occurred, even without the bomb, Truman had written two weeks earlier in his diary after meeting Stalin.

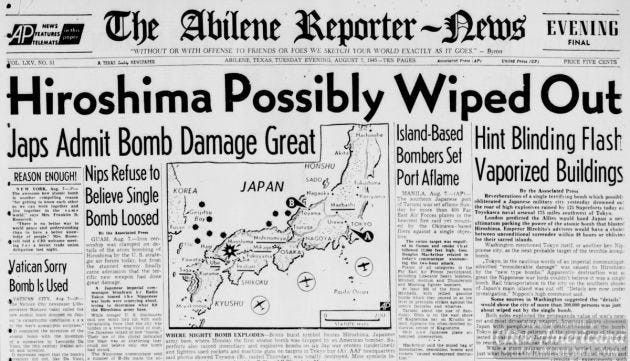

Many Americans first heard the news about the new bomb and the bombing from the radio, which broadcast the text of Truman’s statement shortly after its release. The afternoon papers quickly arrived with banner headlines: “Atom Bomb, World’s Greatest, Hits Japs!” and “Japan City Blasted by Atomic Bomb.” The Pentagon had released no pictures, so most of the newspapers relied on maps of Japan with Hiroshima circled.

One of the few early stories that did not come directly from the military was a wire service report filed by a journalist traveling with the president on the Atlantic. Approved by military censors, it depicted Truman, his voice “tense with excitement,” personally informing his shipmates about the atomic attack. “The experiment,” he announced, “has been an overwhelming success.”

Missing from this account was Truman’s exultant remark when the news of the bombing first reached the ship: “This is the greatest thing in history!”

The Truman announcement of the atomic bombing on August 6, 1945, firmly established the Hiroshima narrative – military necessity with no other options to end the war and countless American lives saved – that endures today.

How the “Hiroshima narrative” has been handed down to generations of Americans – and overwhelmingly endorsed by officials and the media, even if many historians disagree – matters greatly. Over and over, top policymakers, commentators and writers declare, “We must never use nuclear weapons,” yet they endorse the two times the weapons have been used against major cities in a first strike. To make any exceptions, even in the distant past, means exceptions can be made in the future. Indeed, we have already made two exceptions, with more than 200,000 civilians killed.

Why does this matter now? Few may know that the U.S. maintains its official “first-use” policy initiated in August 1945. Any president has full authority to order a pre-emptive first-strike not in retaliation for a nuclear launch in our direction but during any conventional war or even an overheated crisis.

The line against using nuclear weapons has been drawn…in shifting sand.

My photo, girl in Hiroshima’s Peace Park, near ground zero, the memorial to the 125,000 or more dead in the distance.

Greg Mitchell is the author of a dozen books, including “Hiroshima in America,” and the recent award-winning The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood – and America – Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, and has directed three documentary films since 2021, including two for PBS (plus award-winning “Atomic Cover-up”). He has written widely about the atomic bomb and atomic bombings, and their aftermath, for over forty years. He writes often at Oppenheimer: From Hiroshima to Hollywood.