In a press briefing yesterday with State Department spokesperson Victoria Nuland, an unusual question was asked about the morality of the US-led sanctions regime on Iran, which is primarily hurting the population.

QUESTION: Do you have any concern about the effects – the ill effects that the severe depreciation in the currency may have on the Iranian people? When it’s trading – it’s I think something like 32,000 to 1, that inevitably is going to fuel inflation for anything that is imported. Does it bother you that this may hurt the Iranian people?

MS. NULAND: Well, any depreciation of currency is always going to affect the people who use the currency. The issue here are the choices that the Iranian Government is making, and this is the issue, that the Iranian Government needs to make different choices with regard to its nuclear program if it wants to get into a conversation with us about a step-by-step process, including on the sanctions side.

…QUESTION: Now, obviously, the Iranian Government, at least for the time being, is very stubborn; it will remain so. So at what point it becomes really a moral question that the people – 80 million-plus – should suffer so severely because of the stubbornness of their government?

MS. NULAND: Again, we want the Iranian people as well to understand that this is a direct response to the choices that their government has made in the context of the international community offering them a diplomatic way out, which they should take.

Find the full exchange here (I edited out most of Nuland’s evasions). As Antiwar.com’s own Justin Raimondo wrote in 1998 of the sanctions on Iraq: “This exterminationist policy is the logical consequence of a mindset that equates the people of a nation with its government, and therefore punishes the former for the crimes (both real and imagined) of the latter. In the calculus of power, individuals do not count: there are no Iraqis, only the nation of Iraq. The fundamental indifference to justice of the collectivist mentality is underscored by a policy that refuses to distinguish between Saddam and his victims.”

And so it goes for the Iranian regime. Here we have a US official coming face to face with the reality that the US-led economic warfare on Iran is cruelly strangling the population of sustenance, and she tries to claim its the ayatollahs’ fault, not ours. She tells the Iranian people they must suffer for what the regime’s policies are (this is the same regime that Washington continuously decries as undemocratic).

And what is it exactly that Tehran has done to bring on these sanctions? It can’t be punishment for an ongoing nuclear weapons program – US intelligence says it doesn’t exist. Economic sanctions are notoriously ineffective at changing policy in the desired direction anyhow, so why impose them?

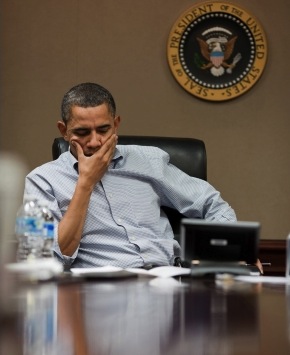

Iran is a regional powerhouse that doesn’t happen to be a US client. That leverage, at a time when Washington is concerned about its own waning influence, is a threat. So sanctions are imposed, as the Washington Post reported in January, to destabilize the regime. Secondly, the Obama administration has been under heavy pressure from Israel and Congress to be hawkish on Iran. And since he’s up for election this year, he’d better be laying the groundwork for starvation and strife in Iran. How else to get reelected?

See here and here for more details on how the sanctions are directly contributing to a collapse of the Iranian economy, and even keeping much needed medicines from the sick and infirm.